- Sophocles

"It's amazing what you see in disclosures. People will go to all extremes to make their performance look better. Comparisons are crazy – you might see something like a comparison of funds returns versus the amount of vanilla bean grown in Tahiti divided by metric tons of iron ore deposits in Western Australia. Voila! We outperformed that number by 3% annually. I'm kidding…..but not by much!"

- "Sonny" Mendez

Value Investing: "A Hell of a Beating"[1]

At the end of each year, the investment management world's conversation inevitably focuses on performance and how well a manager did against their respective competition (the S&P 500, MSCI International Stocks, Bloomberg Barclays Aggregate Index, etc.). This year's discussion has centered on one topic that seems to always be near the top of everybody's list - growth versus value performance. It seems an eternity since value has outperformed growth over a substantial period. Last year was no exception. 2020 was one of the worst years ever when it comes to value strategy versus growth strategy performance. Morningstar reports[2] that:

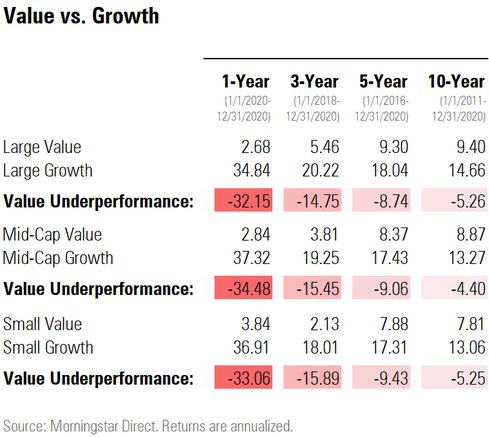

"Large-growth stock funds--which generally invest in companies with strong earnings growth profiles--returned an average of 34.8% in 2020. That was 32 percentage points ahead of the average large-value fund, which has portfolios of companies deemed cheap compared with their potential or are seen as turnaround stories. That exceeded the gap registered in 1999 when growth beat value by 30.7 percentage points. While the value versus growth performance gap wasn't a record for small- and mid-cap stock funds, those groups' average margins were the widest since 1999. And the woeful relative performance for value significantly widened the longer-term return gaps across the board."

The long-term record isn't much better. Over the past one, three, five, and ten year periods, large value, mid-cap value, and small-cap value have underperformed their growth cousins every time. That's right. Not a single time period of outperformance in any market segment in any time period. Here's the very ugly looking chart.

Discussing Failure: Avoid and Abdicate

With value investing performing so poorly, I've been intrigued about how investment managers have been disclosing their results and explaining the reasons for their underperformance. After reviewing about 250 annual reports, investment updates, and articles, the short answer is - most managers don't do anything of the kind. I've found many annual reports discuss everything BUT their returns – discussions that include long term energy policy, the role of climate change in fishing rights, the history of pandemics, the rise and fall of the serf-based economy, etc. Many discuss folksy wisdom like looking at investing as farming - sowing seeds, tending the weeds, and harvesting the profits. Of course, the problem with this is that it might be better to discuss the effects of a ten-year drought filled with biblical hordes of locusts.

At Nintai, we always try to stick to some basic rules in our disclosure policy. First, we seek to be open and honest in our communications with our investment partners. This includes our methodology and our performance. Second, we acknowledge mistakes in a free manner. We discuss the core issues, what went wrong, what we learned, and how we will try not to make the same mistake again. It goes against nearly every business rule, but I enjoy writing about my mistakes. It helps clarify my thinking, and it tells me how my partners view my mistakes. Don't get me wrong. I hate underperformance. I'm as competitive as any manager in the investment industry. That doesn't mean that I can't be honest with myself and truthful with my investment partners.

We recently released Nintai Investments' latest annual performance report. The report discusses 2020 results as well as three years and since inception returns. We compare our return against the performance of the S&P 500 TR index, the Russell 2000 index, and the MSCI ACWI ex-US index. We cite the S&P 500 for the simple reason this is the index most used by the investment world for comparison. We include the Russell 2000 because it is the closest fit to our portfolios' market cap average. Finally, we have the ACWI ex-US because our portfolios hold a considerable portion of foreign stock management assets. We encourage our investors to think of their returns as a blend of these three indexes. We also discuss what investments did best, which did the most poorly, and explain – in detail – why these companies performed the way they did.

We like to think our Annual Reports - along with our Investment Cases and Valuation Spreadsheets - give our investment partners all the information they need to judge our performance and how we communicate with them. We think this type of clarity is critical to maintaining well-functioning financial markets and helps individual investors make well-reasoned decisions to allocate their hard-earned dollars. Later in this document, I will discuss what components are essential in communicating with investors. I will also explain why investment documents are vital in assisting investors in choosing, evaluating, and making decisions.

Disclosure and Discussion: A Working Example

Before I get into those things that I think are important, I thought I'd discuss an instance of financial reports that caught my attention last month. They did so for many reasons, but several stood out. First, the returns for the investment company were abysmal. Second, the reports themselves seem to reflect nothing but good news and the seemingly endless bragging of the fund's managers' investment wisdom. Finally, the report seems to go out of its way to obfuscate and create an intellectual fog about their investment performance relative to the general markets. Before I disclose the company, I should say, in all fairness, this could be many of the funds out in the marketplace. The poor performance, the folksy talk, and the incomprehensible reporting format of performance are all too familiar. I have chosen this investment company simply because its report happened to float across my desk. I have no particular bone to pick with the managers of the investment team.

In this case, the company is Muhlenkamp and Company, based out of Wexford, Pennsylvania. The company was founded in 1977 by Ron Muhlenkamp. In 1988, the company launched a no-load mutual fund (MUHLX). Ron handed the reigns to his son Jeff in 2019.

First, some statistics on the fund. According to Morningstar, assets under management have dropped from $3.47B in 2005 to $181.4M in 2020 (a 94.8% decrease in AUM). Muhlenkamp reports the company's total number of accounts dropped from 289 in 2005 to 48 in 2019 (an 83.4% decrease in accounts).

These decreases have likely been driven by performance, which has been pretty hard to read about from 2005 through 2019. When measured against the S&P 500 TR, the fund's record is the following:

With these numbers in mind, I thought it might help look at what and how Muhlenkamp reports this information to its investors. On its website, there are 8 page tabs including Home, Individuals, Business, Fund, Separately Managed Accounts, Blog, About Us, and Contact. Performance information can be found both in the Fund tab underperformance and can also be found at the end of each "Muhlenkamp Memorandum." A few things jump after reading nearly ten years of reports and memorandums.

- I couldn't find any explanation in any document why returns were so poor. Memorandums were filled with information on the economy, politics, and broader societal issues (like COVID). Yet nowhere could I find an explanation for such overall underperformance (was it due to poor stock selection, lousy market timing, value as a class underperforming growth?). If my fund underperformed (by a lot) on a 3, 5,10, and 15-year basis, I'd feel a deep obligation to explain to my investors how and why performance was so poor.

- Some of the performance data seemed (and this my impression – I have no facts to back this up) to be in the charts to make the funds returns better. For instance, what in the world does the consumer price index have to do in comparing the fund return versus the S&P 500? – other than the CPI number looks a lot smaller than the fund returns.[3] Second, there were columns in the return analysis that I had no idea what they meant or why they were important. For instance, one column was the Composite Dispersion, which is "a measure of the similarity of returns among accounts of the Composite. It is the standard deviation of the annual returns for all accounts which were in the Composite for the entire year." Would an average retiree understand the meaning of any of that and how it impacts their retirement portfolio?

- There is the usual discussion in one of their reports of the sowing and reaping and having a farmer's fortitude and patience. If I had a nickel for every time an investment manager talked about farming, I wouldn't need to be an investment manager. With active value management's performance as it is over the past decade and a half, I'm not sure discussing sowing and reaping is the best approach.

Muhlenkamp's slogan is "Goal-setting, dream-building, future-conquering, financial freedom starts here." They go on to say, "WE'RE NOT YOUR AVERAGE MONEY MANAGERS. We're a scrappy pack of financial nerds and outliers, passionate folks who believe in redefining the industry with data-driven, intelligent investing. We love to smash through the smoke and mirrors that so often mystifies wealth building as we eagerly share our knowledge and decades of expertise with people just like you. We're Your Hometown Team, Forging A Better Way."

Looking at Muhlenkamp's performance over the past fifteen years would suggest they look an awful lot like your average money manager. More importantly, it is unclear what gains have been obtained - from all this smoke and mirror smashing - in both returns and investor knowledge.

As I said previously, I don't have any particular bone to pick with Muhlenkamp and Company. They are pretty standard for a Wall Street investment house (though based in PA). Whether it is caused by the long-term underperformance of value investments in general or something specific to the Muhlenkamp strategy or team, what is evident is that performance is lagging, and disclosure does very little to explain why. It's bad enough their investors have taken their lumps when it comes to a truly horrific case of returns. It seems far worse when these investors are seemingly left in the dark.

So What Can Be Done?

If this type of situation is typical (and value underperformance combined with poor communication is pretty consistent across the investing world spectrum), what can investors do to avoid it? Are there specific items that managers can include in their reports which better educate investors? I suggest there are five particular areas where individuals can look for receiving more pertinent and relevant data.

Does Fund Management Use Fair Comparisons?

One of the first things an investor should look for is fair comparisons when measuring performance. For instance, if a fund invests in small or micro-cap stocks, it's probably not a great idea to measure itself against the S&P 500 index (representing the largest 500 companies). When you see comparisons against indexes with very little in common with the fund, management would seemingly have very little knowledge of market indexes or a willful denial in seeing relevant comparisons. You see this a lot when fund managers are desperately looking for a way to make their returns look better than they really are.

Does Management Openly Disclose and Discuss Mistakes?

Nearly every manager I've ever worked or consulted with has told me discussing mistakes is a form of weakness. I couldn't disagree more strongly. That statement is one of the more egregious I've heard over my years in business. If someone can't confess to errors to themselves and their clients, to whom can they confess? Once an investment manager deceives himself, it isn't long before they start deceiving their clients. Granted, I don't want someone writing me a mea culpa once a month, but the occasional explanation of an error – and description of what they learned – is quite refreshing and assuring.

Does Management Clearly Show Impact of Fees?

This is an area where Nintai Investments needs to do a better job. We charge a rate slightly lower than most actively managed investment services (0.75% annually) but don't describe how much this rate eats into long-term results. I think it would be beneficial to show the difference between an active fund's returns versus their respective index and show the impact on returns by management fee, trading costs, etc. It is certainly possible to show cumulative annual trading costs in an annual report. This is information that could be very helpful to individual investors. It is a goal at Nintai Investments to include this data in 2021 and going forward.

Does Management Discuss Individual Portfolio Holdings?

We think it's constructive for investors to see the investment cases for individual portfolio holdings and an estimated intrinsic value when the stock is purchased/sold in or out of the portfolio. At Nintai, we do this for every stock in every investment partner portfolio. Some have told us they find the information quite helpful and interesting, while others have asked us to stop sending it. Either way, we want to give partners a choice in how much knowledge they have of their investments. After all, it is their hard-earned dollars. We are just fiduciary custodians.

Does Management Clearly Articulate Their Investment Process?

Whenever an investor receives a document from an investment manager, it should assist (in some way) in better understanding that manager's style, approach, and process. We often read reports (much like the infamous "farming sowing and reaping") that tell us nothing about the manager's thinking. This type of writing can help investors better see why a manager made individual decisions and how they feel about their outcomes.

Conclusions

As we head into the twelfth year of value investing underperformance against growth, managers must be able to articulate why their value investment process is still relevant. More importantly, investors want to hear why they should hold tight with managers who have performed poorly over both the short and long term. I've written several times before that underperformance is necessary sometimes to achieve overperformance in the future. If value investing is to avoid the dodo's life path, managers better start explaining how such a theory works and how they expect it to

improve performance going forward. Underperforming on a one, three, five, ten, and even fifteen year time period ask an awful lot of investors' patience. Managers have two choices - increase performance or sharpen their explanations on their investment process and outcomes. Otherwise, as Sophocles pointed out, prudent minds will have had enough of suffering reverses and simply walk away. With losses in AUM like we've seen over the past fifteen years, that might simply be the final straw for many value investment managers.

As always, I look forward to your thoughts and comments.

Disclosures: None

------------------------------------

[1] The quote comes from General “Vinegar” Joe Stillwell of US forces in Burma in World War II. When asked what happened to the allies after the long retreat from Burma he was quoted as saying “I claim we got a hell of a beating. We got run out of Burma and it is as humiliating as hell. I think we ought to find out what caused it, go back and retake it.”

[2] “Value vs. Growth: Widest Performance Gap on Record”, Katherine Lynch, January 11, 2021 https://www.morningstar.com/articles/1017342/value-vs-growth-widest-performance-gap-on-record

[3] Granted, the CPI impacts the purchasing power of the consumer and cuts into returns. However, utilizing this number is similar to comparing the amount of 8 inch turkey subs versus 12 inch turkey subs sold because it reflects the overall strength of consumer spending.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed