- George Savile, 1st Marquess of Halifax

“Perhaps the greatest flaw in the history of castles was thinking moats were a simple defensive tool. Not true! Moats can be both defensive and offensive weapons. In defense, they could be used to force the enemy to attack in a particular spot such as the castle’s most heavily defended area. But a moat might also allow the castle holder to hold one part of the line with fewer men while allowing a sortie (made larger by less defenders needed) on the besieging forces. A great moat allowed flexibility in defense and offense. Great leaders recognized this.”

- Andrew Knighton

Any modern value investor will inevitably use the concept of “competitive moats” in a conversation about a holding in their portfolio. From Graham to Buffett to Klarman, the concept has become a mainstay in the value investing lexicon. I think most value investors would describe a moat as a means of defending existing assets from the inevitable encroachment from competitors. Examples of this might include patents, pricing, or supply chains.

Moats May Be Used Both Defensively and Offensively

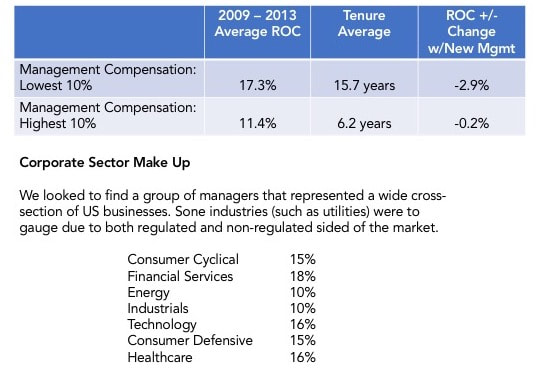

My time at Nintai Partners and now Nintai Investments LLC has taught me to think of moats somewhat differently. We see moats less as a Maginot Line, but rather a strong defensive position as well as a jumping off place for future growth. It seems to me that value investing requires a portfolio holding have both good value (derived from existing assets) and growth opportunities going forward (such as new markets). As examples, I believe a good moat must have strong defensive characteristics (a duopoly/monopoly, pricing advantages, or industry expertise). But it must also allow the company to keep growth perpetually moving forward. Growth strategies are driven by utilizing the defensive strength of the moat to create new opportunities in adjacent markets or new products. Confident in the defensive nature of its core industries, the company can utilize its product and services in industries similar to their core customers. As an example of this, Nintai looks for companies with high return on capital in both existing products and services as well as new initiatives.

A Working Example: Veeva Systems

An example of a moat that works both defensively and offensively is Nintai Investments holding Veeva Systems (VEEV). Veeva Systems provides cloud-based software to customers in the life sciences industry for customer relationship, content, and data management. Veeva CRM is a suite of applications that help pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies market and sell products to healthcare providers. Veeva Vault, a product built on proprietary software, is a cloud-based application built to manage content and associated data. Veeva’s first-mover advantage has allowed them to dominate in life sciences with an estimated 65-70% market share.

By deeply embedding themselves in most aspects of life sciences drug discovery, development, and promotion/sales, the company has a deep competitive moat that can hold off competitors for at least the next decade or two. Utilizing a Salesforce customer relationship management (CRM) platform, Veeva has become the de facto CRM leader in life science sales and promotional teams. In addition, Veeva has created its own proprietary platform to assist life science companies work with data from drug discovery all the way to Phase IV (label expansion) trials. These products and services can be described as “defensive” in nature through their ability to hold and expend their life sciences customers.

Because the company’s systems are cloud based and agnostic to underlying systems, Veeva can use its moat to go on the offensive and seek out similar industries to life sciences (chemicals, food products, industrial manufacturing, etc.). Veeva Nitro – the company’s latest product launch – is a cloud-based data warehouse system that works with their CRM platform and analytics capabilities. These new offerings are meant to explicitly sortie outside their life sciences castle and move into such adjacent industries. As the company defensive moat continues to keep Veeva dominant in life sciences, it funds and creates opportunities to move out offensively in fronts which will drive growth over the next several decades.

Veeva announced earlier this year it had been awarded contracts with two chemical companies and 1 industrial manufacturing facility. These new efforts are considered bridgeheads to the new industries targeted outside life sciences. Veeva’s goal is to create two new industry “castles” with deep competitive moats within the next 5 -10 years. By utilizing the same products and services (customized to meet the needs of these two new industries), Veeva believes it can leverage existing systems quite quickly into dominant positions.

Deep Moats Can Prohibit Growth Too

A company with a deep moat can sometimes end being a value trap as management hunkers down and has no inclination to sortie out to seek new markets. An example of this is Value Line (VALU). I’m showing my age when I say I can remember spending days reading the Value Line reports on individual stocks and mutual funds. In its day, it was the Encyclopedia Britannica of investment research. With the onset of the digital age, the company made almost no effort to digitize its data or move to a web-based research model. This is a company Nintai would normally be salivating over. The company generates return on capital of 31%, return on equity of 36% and return on assets of 17%. The company has no debt and yields 3.6%. What’s not like?

Unfortunately, the Bernhard family (Arnold Bernhard started the company in 1973. His daughter Jean Bernhard Buttner ran the company as well) through its family trust never saw any reason to take competition seriously from such companies as FactSet Research (FDS) or Morningstar (MORN). Hunkered down in their castle, company management saw revenue drop from $85.3M in 2004 to $35.9M in 2018. Even with a major restructuring in 2010, investors have seen a cumulative -4% return over the last 10 years (not including dividend reinvestment).

Value Line’s management has squandered an extraordinary asset in its Value Line reports by allowing a deep competitive moat to trap them within their own lines. Eventually, any moat can be filled. Without the ability to see outside the walls of their castle, sometimes the best companies play defense for far too long. Without any plan for growth, Value Line has become the walking embodiment of a value trap.

Conclusions

Without a doubt, I would rather invest in a company with a moat against one that has none. As a value investor though, that only tells half the story. A moat is only part of a fixed defense that allow for companies to continue building the moat or simply expand and build a new castle. Sitting in their fortifications, sometimes management can get overconfident and live off the safety of their moat for too long. Remaining in leadership means constant evolution in your business model so that as one moat may be filling, you might be thinking how to build an entirely new one. As the Marquess of Halifax said: look to your moat. But also look for growth.

As always I look forward to your thoughts and comments.

DISCLOSURE: I currently own Veeva in individual and institutional accounts. Morningstar (MORN) and FactSet Research (FDS) are former holdings of Nintai Partners.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed