- Andrew Jackson

“We don't have a monopoly. We have market share. There's a difference.”

- Steve Ballmer

A lot has been written about biopharma and drug prices in the United States. I’d like to suggest a new way of thinking about the pharmaceutical industry. Think of the largest pharmaceutical companies as a medium risk/medium reward bond. (Not literally. This is a concept only!). I suggest this for three reasons - pharmaceitical dividends, record low interest rates and pharmaceutical drug pricing.

First, pharmaceuticals have a long history of generous and increasing dividends. As I will discuss further on in the article, most of the largest pharmaceutical companies have shown steady growth in their dividend for the past 10 years, even in times of declining revenue.

The second started as the central banks of countries around the world have lowered their discount rates to the point that for the first time, we are seeing negative interest rates at a global level (excluding the US if Janet Yellen has her say). The impact of this is enormous. For net savers - individuals and pension funds alike – the need to stretch for yield becomes essential. Dividend paying stocks, along with utilities, have been some the best performing stocks in the US markets. As steady dividend payers, the largest pharmaceuticals represent a decent yield that far exceeds the interest rate on a 10-year Treasury note. Many will point out the risk relative to a pharmaceutical and the US treasury is quite wide. I would agree with this - to a certain extent. And this brings us to our third point - pharmaceutical drug pricing.

In this week’s Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), researchers from Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School published an outstanding article on the core factors surrounding US drug prices[1]. In the article, the authors point out five major characteristics of US pharmaceutical drug prices.

US Drug Pricing is Unique in the World

The United States over the past 35 years has spent a great deal more on drugs than the rest of the world. For instance, in 2013, per capita spending on prescription drugs was $858 compared with an average of $400 for 19 advanced industrialized nations. The spread is even greater for the true blockbuster drugs (meaning revenue of greater than $1 billion). For the top 20 drugs, prices were roughly 3 times greater in the US than in Great Britain. Even taking into account rebates (discounts that are negotiated between the pharmaceutical and payers such as Medicare, Medicaid and private insurers such as Anthem or United Health), drugs generally cost 10-15% more than Canada, France or Germany. Those blockbusters we just mentioned? Sometimes 150-200% more. Our business model in the US is simply unique.

Patents and Pay-for-Play Cause Government Created Monopolies

Under US law, pharmaceutical companies are granted patents for 20 years (or more), guaranteeing exclusivity for their drug. This can be somewhat offset by competitive offerings (think Sprycel versus Gleevac) that allow payers to play each pharmaceutical against their competitor. Pharmaceutical companies will look to extend patents by obtaining an extension through patenting the coating, or even the color, of the pill. But many therapeutic diseases (known as orphan diseases) have only one treatment option. In these cases, many pharmaceuticals will create a pay-for-play scenario with a would-be generic drug manufacturer. In these cases, the pharmaceutical will reach an agreement with the generic company to not produce a generic version. Why does this matter? In most cases, the generic version of a drug is 55-75% below the branded drug.

FDA Approvals Are Just as Hard on Generics

Each pharmaceutical drug approved by the FDA goes though an extensive clinical trial process to show efficacy, safety and delivery methods. This process can take as long as seven years. For generics, the FDA plays by the same rules, though you would think an exact replica of the branded drug would be much quicker. There you would be wrong. The average approval process for a generic is 3 to 4 years. This time frame essentially extends the pharmaceutical’s opportunity for this additional period. No generic means no price reduction.

Rules and Litigation Can Drive Up Costs

A lot of money could be saved when a patient goes to the pharmacy to fill a prescription. If a generic is available (remember: these are FDA approved replacements), then the pharmacist could switch from a branded heart medicine to its generic version. Not so fast, 26 states require the pharmacy get a written consent to make the switch. The cost? The aforementioned heart medicine (in this case Zocor) cost Medicare nearly $20 billion in in 2006 simply because pharmacies could not get patient consents.

Drug Pricing is Based on Competition, Not R&D Costs

You will often hear the pharmaceutical industry trade group PhRMA talk about the costs of R&D driving the ultimate costs of their members’ product. And there is some truth in this. It is extraordinarily expensive to bring a drug to market. Estimates range from $880 million to $1.4 billion. Not chump change. But products are priced mainly on two things – what your competition charges and/or what the market will bear. We are learning there are limits to the latter. Gilead’s pricing for its hepatitis C therapies drew a withering response from payers. Open the paper on almost any given day and you can read about some supposed outrage being perpetrated against patients.

So What Does This Mean?

To get back to my thesis of seeing large pharmaceuticals as a substitute for bonds, the following are my reasons for proposing such an idea.

Growth Has Been Slow….But Steady

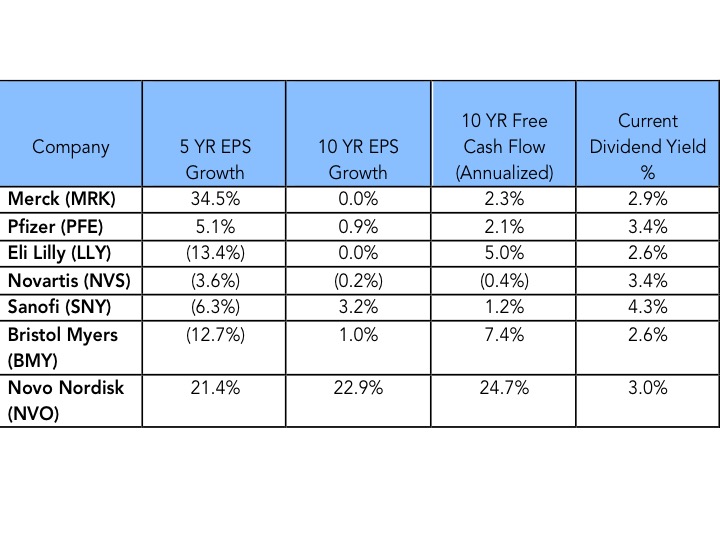

When you take a look at large pharmaceuticals over the past 5 and 10 years, several things stick out. First, the last 10 years have been the most difficult for these companies in the past half century. The low hanging molecules have gone off patent and many companies are just now getting back to growth. This can be seen in both the 5 and 10 year EPS growth rates. But quite amazingly, only one company has seen free cash flow decrease over the past 10 years. While markets were difficult, large pharmaceuticals, through a combination of cost savings and annual price increases, continued to slowly grow free cash flow over the past decade. This has meant that every one of these companies has increased their dividend over the past 10 years[2].

For the reasons cited in the JAMA article, the ability of large pharmaceuticals to drive revenue and dividend growth has all the makings of an extraordinarily wide moat. With so much dependent on Congressional legislation, it is unlikely these factors will change much at all (or any) over the next decade. Pressure from payers will likely hold prices down somewhat, but overall increases are baked into their fee structure models.

A New Stage of Growth Has Arrived

Areas of growth have emerged for large pharmaceutical companies such as onco-immunology, diabetes, hepatitis and vaccines. These therapeutic classes not only have high growth rates (from 2016-2022 annual growth rates are estimated to be 9%, 8%, 6% and 5% respectively). This type of growth will likely prove to be significant drivers for revenue and dividend increases over the next decade.

Conclusions

Faced with a historically low interest rate environment, savers are faced with the possibility of paying the government to hold their cash. This is obviously not a wise course of action for pension plans or individual retirees faced with growing cash needs. By changing the lens slightly, it’s possible to see how large pharmaceuticals could provide the opportunity to replace government bonds with an “equity bond” that yields far more and provides a great deal of safety of their principal. Note, I say a great deal. There is really no way to reduce the risk of a publicly traded equity to the level of a government bond. But extreme environments demand innovative thinking. For those faced with record low yields, this might be a risk worth taking.

Disclosure: Both the Nintai Charitable Trust and some individual accounts at Dorfman Value Investments own shares in Novo Nordisk (NYSE:NVO)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed