Growth and Value: The Foundation of Fuzzy Thinking

One of the things that Warren Buffett has spoken about many times is the fact that making the distinction between growth and value can lead to fuzzy thinking. Buffett frequently makes the point that all value investing is about growth investing. In his 1992 Berkshire Hathaway Annual Report, he wrote:

“Most analysts feel they must choose between two approaches customarily thought to be in opposition: "value" and "growth." Indeed, many investment professionals see any mixing of the two terms as a form of intellectual cross-dressing. We view that as fuzzy thinking (in which, it must be confessed, I myself engaged some years ago). In our opinion, the two approaches are joined at the hip: Growth is always a component in the calculation of value, constituting a variable whose importance can range from negligible to enormous and whose impact can be negative as well as positive.”

He further elaborated his thinking in his 2000 Annual Report writing:

“Common yardsticks such as dividend yield, the ratio of price to earnings or to book value, and even growth rates have nothing to do with valuation, except to the extent they provide clues to the amount and timing of cash flows into and from the business. Indeed, growth can destroy value if it requires cash inputs in the early years of a project or enterprise that exceed the discounted value of the cash that those assets will generate in later years. Market commentators and investment managers who glibly refer to "growth" and "value" styles as contrasting approaches to investment are displaying their ignorance, not their sophistication. Growth is simply a component - usually a plus, sometimes a minus - in the value equation.”

I bring up the distinction between growth and value because I made a fundamental mistake recently in my calculation of the value of Veeva (VEEV) - which led me to sell the stock from client portfolios. My error – which I will discuss in much greater detail below - was thinking that growth in the stock price was rising (and would continue to rise) at a faster rate than my estimated intrinsic value ever could. That is to say Veeva’s valuation would never keep up with its growth.

A Little Background

Veeva Systems was a group of individuals who worked with Salesforce (CRM), a customer relationship management (CRM) software provider. This group believed their expertise in the pharmaceutical market could lead to high growth and significant market share. The company was a success from the beginning. Since 2011, Veeva grew revenue per share from $0.25/share to $5.52/share in 2019. The past 5 year annual growth rates for revenue, earnings per share, and free cash flow have been 16.6%, 55.7%, and 40.2% respectively. The company averaged return on capital in the low 80% range and grew free cash flow margins from roughly 15% in 2011 to nearly 42% by 2019. The company has never carried any short or long-term debt and increased cash/marketable securities on the balance sheet from $17M in 2012 to $1.43B in 2019.

Veeva also happened to be in a market vertical where Nintai Partners had deep experience. Most of Veeva’s clients were Nintai’s consulting clients and their work in informatics coincided with Nintai’s core competency. We deeply respected Veeva’s management, their product and services, and their market strategy. In essence, Nintai Partner’s legacy knowledge allowed the new Nintai Investments LLC to be comfortable partnering with an outstanding company and management team all in a growing market.

The Decision (or How We Blew It)

Nintai Investments LLC had owned Veeva since opening its doors (it had been a holding in the Nintai Charitable Trust since 2005). We originally purchased the stock in February 2018. In May 2019 - after a blow out quarterly earnings announcement - we sent out the following to our investment partners.

-----------------------------------------------------

To Our Investment Partners:

Yesterday, Veeva (VEEV) announced Q1 earnings. They were superb. The stock is trading up 14% today. Q1 revenue grew 25% year over year to $245 million, while normalized EPS grew 52% year over year to $0.50. Subscription revenue increased 27% year over year, while services revenue increased 18%. Deferred revenue increased 26%. Operating margins increased from 32% to 38% compared to last year. Bookings and service revenue look outstanding. Guidance for the remainder of 2019 was ahead of our expectations. We expect to increase our estimated fair value by roughly 8% bringing it to around $100/share.

The position has returned 168% since our initial purchase in February 2018. The stock currently trades at roughly a 54% premium to our estimated intrinsic value. At that level we frequently sell out of the entire position. However, because of the uncertain potential of adjacent market opportunities (the company announced deals in chemicals and consumer goods recently), we only sold 40% of our existing position and will retain a position in the company.

Please feel free to email or call with any questions. My best wishes.

Tom

--------------------------------------------------

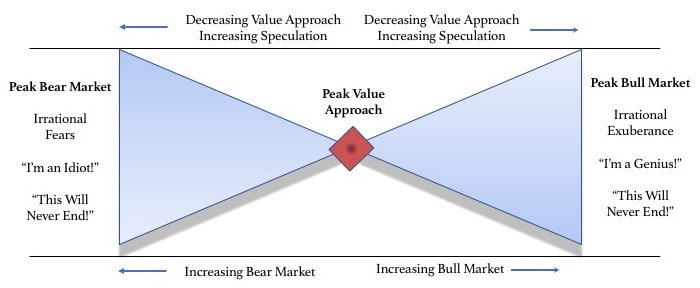

So far our investment partners had nothing to complain about. We had a holding with outstanding returns though now trading at a significant premium to our estimated intrinsic value. Here was the rub however. Conservative value investment theory would have us sell the position at such a premium. No matter how successful we felt the company could be, we felt we couldn’t be guilty of recency bias or hold on to the stock simply because of how well it had performed in the past. Be ruled by the head and not by the heart.

With 20/20 hindsight our mistake was startlingly obvious. In our “head-not-heart” mind set, we simply couldn’t believe a review (no matter how deep) in our valuation process would increase the valuation greater than the increase in the price. So - utilizing our supremely confident “we-must-be-supremely-heartless-and-coldly-rational” attitude, we sold out the entire position by end of July 2019. We congratulated ourselves on locking in a 168% return for our investment partners and began looking at new opportunities in which to allocate this capital.

What Happened Next

After selling the stock and placing it on the watch list, Veeva came up for review relatively quickly. At Nintai, this annual process is quite extensive with a top to bottom breakdown of our investment case. Everything that can be used to better understand the competitive advantage and market moat is broken down with in-depth research. We look at product pipeline to sales force effectiveness, market satisfaction and adoption rates, customer reviews and purchasing budgets, regulatory filings and approval calendars. We also break down the company financials trying to get a deep understanding of the components that make up cash flows, income statement, and balance sheet. Particular focus is spent on capital allocation and free cash flow generation.

Without going into all the details, by the end of our review it became very clear we needed to seriously adjust our valuation upwards. In fact, the increase was so large we sent out a new update (barely two weeks after sending out why we felt compelled to sell the position).

------------------------------------------------

We spent this past Monday and Tuesday speaking with Veeva management, their largest customers, industry thought leaders, and regulatory officials. This completed our nearly two week review of the business, including our annual deep dive on competition, market growth, etc. After reviewing our findings it became clear that we had seriously undervalued the company. Our revised valuation went from roughly $110/share to nearly $182/share. We have to say that this is the largest adjustment in intrinsic value we’ve ever made. Since July 15th Veeva’s stock price has dropped from $175 to today’s (September 13 2019) price of $139. This represents a 21% drop. At this price the stock trades at a 23% discount to our estimated intrinsic value.

-----------------------------------------------

John Maynard Keynes famously never-said[1], “When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do, sir?”. It’s pretty wise advice no matter who you attribute it to. With as straight a face as we could muster, Nintai announced we were reversing course and adding Veeva back into the portfolio. It certainly wasn’t a banner day at Nintai world headquarters, but at least the facts backed us up……again.

What Can Be Learned

I could probably write a book just on the errors from the “Veeva Adventure” (as we refer to it now). That will have to wait for another day. For now, let me summarize the findings that are most applicable to every day investing theory and practices.

Don’t Ever ASSuME (You Know How the Rest of That Goes)

In my value investment trained mind, I had made the distinction that Warren Buffett had clearly warned led to fuzzy thinking. It is possible to have a value investment that has two seemingly contradictory attributes - high growth in revenues and free cash and trade at a significant discount to intrinsic value. The value investing world will not end when the two reside next to each other. It’s a lesson I seemingly need to (re)learn every couple of years.

Don’t Get Over Confident

When you start to think you know enough about the company or its markets without looking at new data, then you’ve got a real problem. Market dynamics can change by the day, so an investor should always base decisions on the latest well-researched statistics. The fact that I could be off by such an extent on Veeva’s valuation was an example of clear arrogance. Just because I knew a lot about the company’s past didn’t mean I was a greater predictor of its future.

If You Base Your Decisions on Facts, Then Be Damn Sure About Your Facts

One of the reasons why I always write an investment case for a potential investment, then turn around and write an anti-investment case, is to make sure I’ve seen both sides of the arguments and the facts support one more than the other. This means I have to know my facts cold. This also means I need to check and double check my facts. Not only was I guilty of intellectual arrogance when it came to Veeva, sadly I was guilty of intellectual indolence as well.

Conclusions

Being able to identify mistakes and finding the cause is really only half the battle. The second part is creating processes to prevent these types of errors from happening again and being able to verbalize what happened to individuals outside the decision process. This might include your investment partners, your Board of Directors, and you, the reader. I keep a running list of errors I’ve made in my investment process since 2004. That list includes 77 specific errors. Each one is identified, discussed, and then a solution is listed next to it. I’m glad to say I’ve only repeated a total of 6 errors or roughly 8% of the total list. Unfortunately, the underlying cause of the Veeva case is a repeat offender. In my next article I thought I’d discuss other cases similar to this, what solutions I’ve employed, and why I think they have failed.

Until then, I look forward to your thoughts and comments.

Disclosure: Portfolios that I personally manage own Veeva.

[1] The quote has been attributed to Keynes for decades. Unfortunately - as Jason Zweig points out in a WSJ article - there is no direct evidence Keynes said ANYTHING like it. Keynes’ biographer, Lord Robert Skidelsky, believe the quote (along with the other gem “the market can remain irrational longer than you can remain solvent”) was “most likely apocryphal”.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed