How Long is Too Long?

We were reading two very interesting articles in the past few days. The first was The Science of Hitting's "Process vs. Outcomes, Revisited "of April 7th, 2015 and the second was "False Discoveries in Mutual Fund Performance: Measuring Luck in Estimated Alphas”, by L. Barras, O. Scaillet and R. Wermers[1].

Each of these articles helped provoke thinking around the office that finally settled on one specific question: how long is too long for your investment managers to underperform? This is quite relevant today as many value investors - including Nintai - have underperformed the greater markets over the last three (3) year period. With said, how long of a leash do you think is adequate to understand whether your managers are successful or simply not cutting it?

There's no set answer to this question. Traditionally endowments and pension funds have been very hesitant to replace underperforming outside investment managers. This is probably wise. In a great 2008 study[2], Amit Goyal and Sunil Wahal demonstrated that “excess returns after terminations are typically indistinguishable from zero but in some cases positive. In a sample of round-trip firing and hiring decisions, we find that if plan sponsors had stayed with fired investment managers, their excess returns would be no different from those delivered by newly hired managers”. That either reflects poorly on the plan sponsors, investment managers, or both.

Retail investors are vastly different. They are capable of surprising agility in their hiring and firing of investment managers. The Quantitative Analysis of Investor Behavior[3] shows the average mutual fund equity investor holds a fund for an average of 3.3 years. For bond fund investors, the average holding period is less than 3 years. It is estimated that retail investors look to begin selling their mutual funds after two quarters of underperformance and individual equities after just one week of losses. Fair weather friends indeed.

And yet there funds and managers who buck this trend. An example of this is Ken Fisher of Fisher Investments. Mr. Fisher comes with the following recommendations:

“He has been writing Forbes' prestigious "Portfolio Strategy" column for over two decades, making him one of the longest running columnists in the magazine's 85+ year history”.

“During his many years of money management and market commentary, Ken has distinguished himself by making numerous, accurate market calls, often in direct opposition to Wall Street's consensus forecasts”

“He is the son of legendary investor Philip A. Fisher, and Ken is the only industry professional his father ever trained”.

Pretty heady stuff. Writer of several books and talking head on every major business network, Mr. Fisher is omnipresent. He’s been so good at appearing as a true market guru his assets under management have increased from $3B in 2003 to $47B in 2015.

The only problem with this picture is that his investment calls have underperformed both their bogey and the S&P 500 for nearly every measurable period. As an example, his Purisima Total Return Fund (PURIX) has underperformed the S&P 500 in the 1 Year, 3 Year, 5 Year, 10, Year, and 15 Year time frame. When compared against Morningstar’s recommended bogey of MSCI ACWI Ex US (World Stock) the fund has underperformed its 3 Year, 5 Year, 10 Year, and 15 Year measured periods. Yet by 2015 this fund over $300 million under management.

My goal isn’t to pick on Mr. Fisher. I’m sure he has a reasonable answer for this performance. I bring it up because it seems to fly in the face of rational investment theory. Why would a fund grow assets for so long with such a pedestrian – if not losing - record? How long is too long for investors in the Purisima Total Return Fund?

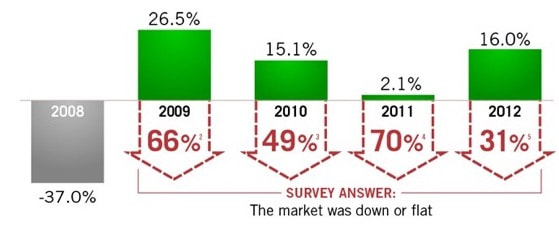

Part of the answer lies - as always - in investor psychology. One of the great understandings in behavioral finance is that if you appear to a winner, then you are a winner, and will likely always be a winner. In other words what goes up will continue to go up. Conversely, the same goes for funds or company stocks that suffer truly horrible losses. The lasting view of investors is that the fund/equity will always be a loser. A great example of this is the annual study conducted by Franklin Templeton[4]. Investors were asked about stock market performance following the crash of 2008. The S&P 500 was down 37% that year but up 26.5%, 15.1%, 2.1%, and 16% in the next respective four years. Investor impressions were exactly the opposite as seen in the graphic below. Respondents saw these years as additional losses ranging from 31% to 70%.

For individual investors and money managers alike there are some key lessons to be learned as we think about the question of “how long is too long”?

Trends Are Your Friends…Until They Aren’t

As prototypical homo sapiens we are particularly susceptible to riding trends that either work or don’t work for far too long. As money managers we fight it every day. Examples include holding that stock of a company that you insist still has upside potential because it has always gone up or never investing in an industry because thirty years ago it was ridiculously unprofitable. The ability to test your thesis and assumptions on a regular basis is the only way to avoid falling into these traps.

The Only One With the Correct Answer is You

Reaching a definition of “too long” is a wholly subjective answer. Not everyone’s will be the same. For investors in the Purisima Total Return Funds 25 years is not too long. For others the time frame may be days rather than years. In the final analysis only you can make the decision and definition about “too long”. Dependent upon your risk level, investment strategy, and personal needs, you will need to decide if or when to pull the plug.

Data Must be the Core Decision Tool of “Too Long”

At Nintai underperformance or short term stock drops are absolutely painful. A recent example was our recommendation of Computer Programs and Sciences (CPSI) and having it drop 14% that very day. For us one day of ownership felt like too long. Another was our ownership of Manhattan Associates (MANH) and our behavioral and emotional difficulty in recognizing the stock was so far overvalued we need to sell out of our total position. These are the moments when we must ruthlessly employ data. Whether we felt holding for reasons of loss or gain, the data will dictate what is too long (or too short) in regards to investing your hard earned capital. Equally, fund investors should employ hard data – historical returns, costs, and portfolios to decide whether you have partnered with a financial manager for longer than the data recommends.

Conclusions

No matter what people will say, there is simply no mathematical formula that can definitively tell how long is “too long”. But we can say is that some of the worst decisions we’ve made in regards to this have been emotional decisions rather than a data driven process. Deciding whether your financial advisor or manager has had enough time to prove them selves is a particularly personal decision. A blend of what allows you to sleep at night, your financial goals, and your investing knowledge will dictate an answer to that vexing question. That - combined with historical data – will help investors make an informed decision.

As always we look forward to your thoughts and comments.

[1] “False Discoveries in Mutual Fund Performance: Measuring Luck in Estimated Alphas” L. Barras, O. Scaillet and R. Wermer, July 2006

[2] “The Selection and Termination of Investment Management Firms by Plan Sponsors”, Amit Goyal and Sunil Wahal, Journal of Finance, August 2008

[3] The full report can be found at http://www.qaib.com/public/default.aspx (Membership required)

[4] Franklin Templeton “Investor Sentiment Survey”, 2010-2013

RSS Feed

RSS Feed