Ieyasu Tokugawa

Tokugawa Ieyasu would have likely had a love/hate relationship with Ben Graham’s Mr. Market. On one hand, he had very little sympathy for those who acted rashly because of a lack of emotional control. At the same time, his lifelong success was bred from taking advantage of such individuals. If this sounds similar to a certain Mr. Warren Buffett indeed it should. In these beginning weeks of 2016, the ability to restrain one’s inclinations (in the words of Ieyasu) is a tremendous attribute to the value investor.

Patience as Optionality

Tokugawa Ieyasu saw patience as the ultimate in optionality. For managers, optionality is defined simply as ‘the ability to have, locate, or define options from existing conditions. These options can be defined by space, time, or values such as resources or finances”. A famous Japanese folk saying states, “to catch the biggest fish one must cast the longest line”. The ability to store up such a length of line, deploy it at the most opportune moment, and the ability to endure the long lead-time are rare human attributes. But they are some of the most common traits in successful value investor methodologies. There is a story about the three unifiers of modern Japan. Oda Nobunaga was known for his violent streak, Toyotomi Hideyoshi was known for his skill in negotiating victories, while Tokugawa Ieyasu was known for his patience. In the story a mockingbird sits in a tree but won’t sing. Oda says of it won’t sing he will kill it. Hideyoshi says he will find a way to make it sing. And Ieyasu says he will wait for it to sing. While likely apocryphal, the story sums up each respective leader’s world-view. More importantly, it should be noted that Oda was assassinated at the age of 47 never having united Japan. Hideyoshi finished Oda’s work by creating a unified Japan by the end of the 16th century but lost everything by having no heir old enough to claim the shogunate upon his death.

In a recent article on his blog[1], Tren Griffin quoted Carl Icahn as saying; “The cardinal rule is to have enough capital at the end of the day. In takeovers, the metaphor is war. The secret is reserves. You must have reserves stretched way out ahead. You have to know that you could buy the company and not be stretched.” As Harold Geneen said once: “The only unforgivable sin in business is to run out of cash.”

All of these quotes and stories have one thing in common – utilizing time and resources (in this case cash) in the game of life and investing. Tokugawa’s method of constraining one’s inclinations - or having patience - means having both a balanced emotional response and the wherewithal to put that patience to work as a focused optionality. Think of it as three-dimensional put and call options strategy capable of being struck at the most advantageous time, place, and price to you as an investor.

Emotions in Achieving Patience

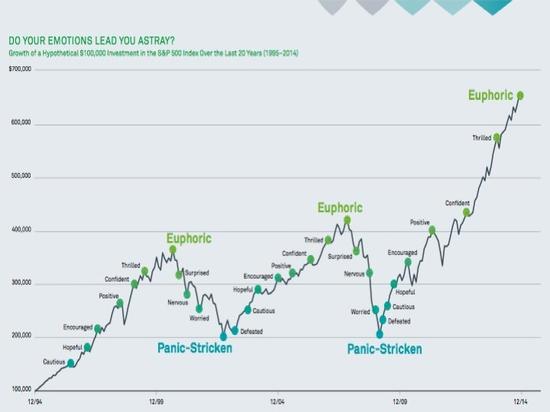

Tokugawa understood that mastering emotions - not eliminating them - was the key to success. Generally, untamed emotions nearly always lead to bad decisions. In his eyes, the worst possible scenario was making the wrong choice at the wrong time based on the wrong emotion. For instance, many of us are faced in the beginning of 2016 with considerable losses in our holdings. By making decisions based on fear, we will likely be making a very human - but also a very poor - decision. Many of us have seen the classic emotive view of market investing. I’ve attached a version (a particularly vivid one from Blackstone) showing the emotions of the average investor laid over returns for the period 1999 - 2013.

I should say right up front maintaining your emotional (and cash!) balance in down times is much harder than in the days of euphoria. Study after study shows that humans feel loss far more intensely than gain[1]. This natural inclination can cause an individual investor to entirely lose the one great asset they have over professional money managers – the ability to look downfield and exploit opportunities by keeping their options open.

The Samurai Stock Market

So what’s an investor to do in these down days of 2016? I’d suggest you get in touch with your inner Tokugawa and develop his core thesis on patience. Don’t ignore your emotions – simply get better control of them. Use your inherent advantages as an individual investor to create market optionalities AND opportunities that simply don’t exist for money managers who feel they must be fully invested all the time. Most professional money managers act far too similar to Oda (“if the shares don’t increase in price immediately I will sell it”) or Hideyoshi (“I’m smart enough to know which stock will rise in price”) versus having the patience of Tokugawa and let management compound value over time.

When many individuals think of bushido (Japanese for “The Way of the Warrior”), many misplace the thrill of war on the samurai class of Tokugawa Japan. In reality, the great samurai saw combat as an option to accessing or gaining power. Those who stayed in power the longest recognized that by practicing patience they could avoid war altogether. This optionality was a powerful tool to have available but terribly costly in its employment. By mastering the seven emotions, leaders like Tokugawa and his decedents made best use of their limited capital.

Conclusions

How did Tokugawa’s patience work out? Pretty well actually. At the Battle of Sekigahara his forces routed the opposition and put him - and his family - in the position to rule Japan for the next 250 years. To put that perspective imagine George Washington’s direct descendants are still President today in an unbroken link since 1789. How did he achieve such results? By maintaining roughly 25% of his troops in reserve and unleashing them at the height of the battle. These reserves - or force optionality as they are called in today’s lexicon - made all the difference to Tokugawa. As we are faced with some significant losses in the beginning of 2016, such reserves might just do the same for you.

[1] Loss aversion was first demonstrated in Kahneman/Tversky’s classic “Choices, Values, and Frames”, American Psychologyst, #39, 1984. Though over three decades old as I write, this article should have a front and center seat on every investor’s or money manager’s desk.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed