- Anonymous

"The ideal business is one that earns very high returns on capital and that keeps using lots of capital at those high returns. That becomes a compounding machine."

- Warren Buffett

Revisiting Weighted Average Cost of Capital

One of the most interesting stories in the past 18 months has been the lack of discussion about the rapid fall and rise in the US 10-year Treasury yield. It isn't my intention to discuss the reasons for the changes or their meaning for the economy, but rather its simple impact on stock valuation. Such increases and decreases mean that any borrower will see a dramatic effect on their average cost of capital. With rates peaking at roughly 3.1% in October 2018, companies saw the rate drop by approximately 80% over the next 18 months. In less than six months, the 10-year US Treasury rate rose from 0.53% in October 2020 to 1.63% in March 2021.

It's hard to overstate the impact these swings should have on the valuations of publicly traded equities. For those who use a discounted cash flow model (which we do at Nintai investments), a vital component in getting to an estimated intrinsic share value is calculating a company's average cost of capital. In our models, the most significant impact on that calculation is the 10-year Treasury yield.

Before I get into that, a quick overview of United States Treasury note yields, how they are calculated, and their role in our financial markets. The Treasury note yield is the current interest rate paid on the 10-year United States Government Treasury note. The government pays the yields as interest for borrowing money through debt sales at monthly auctions. When the auctions take place, the government sells a specific dollar amount of bills (duration less than one year), notes (sold in 2, 3, 5, 7, and 10-year maturities), and bonds (30 years, reintroduced in February 2006). For the sake of this discussion, we are only interested in the 10-year note.

Once the debt has been sold, bills, notes, and bonds are traded on public markets, with investors buying and selling this debt and creating a market-driven interest rate. The rates generated in these markets for the 10-year note are vital in the financial markets. For instance, it is the proxy for many financial services such as mortgage rates. It is also used in determining interest rates on credit card debt. Trillions of dollars of financial instruments are affected by changes in these rates.

The 10 Year Treasury Yield and Stock Valuation

For value investors, the 10-year note's yield has (or should have) an enormous impact on the valuation of publicly traded equities. When an investor looks to value a business, there are two calculations that play a tremendous role in estimating its long-term intrinsic value. The first is the company's return on capital (ROC). The second is its average weighted cost of capital (WACC). One of the most critical aspects of finding quality in a potential investment opportunity is a having a high return on capital. At Nintai, we look for companies that achieve 15% or greater ROC over the past decade. ROC is an excellent tool for getting a grasp on how well management teams allocate capital. But it's only half the equation (literally and figuratively!). Equally important is the company's weighted average cost of capital. A company always wants ROC to be significantly greater than WACC. It doesn't matter if they can generate an ROIC of 15% if their cost of capital is 18%. (Hence the opening quote about losing a small amount on each transaction, but making up for it in volume)

The weighted average cost of capital is one of those topics that inevitably leave peoples’ eyes glazed over when you bring it up. It's like discussing the interest rate you will be paying on that brand new sports car in the driveway. Not many people insist on diligently reading the term sheet. Instead, most dream of taking those sharp turns or doing racing changes on the interstate before trying to measure how the cost of capital might impact the long-term value of that new sports car.

Return on Capital versus Cost of Capital: A Simple Example

Let's use an example of an investor choosing to use cash obtained from a credit card advance to invest in stocks. It sounds crazy, but I've seen things more insane in my investing career. For example, let's start with the cost of capital. A cash advance can be obtained for the average credit card owner with two main items driving calculating the cost of that capital.

First, the card company will charge a fee which is generally based on the percentage of the transaction. For the sake of this exercise, let's assume the cash advance is $25,000. According to CNBC, the average transaction charge usually is between 3 – 5% of the advance amount. For this case, let's cut it down the middle and call it 4%. In this example, the individual will pay $1000 for the advance (25,000 x 4%). Second, the credit card company charges an annual interest rate fee on the balance. Let's assume the individual is not planning on paying off the balance for the first year but pay any fees and interest charges. According to the website creditcard.com, the average interest rate charged by the credit card company is 16.15%. For the first year, the individual will pay $4,037.50 (25,000 x 16.15%).

In this instance, cost of capital would be $1,000 + $4,037.50 or a total of $5,037.50. Put in the Wall Street terms, the cost of capital would be 4% + 16.15% or 20.15%. Of course, this number means nothing until we calculate the return on capital and see how the two numbers compare.

To calculate return on capital, let's assume the individual wants to invest in a hot-shot stock growth fund that she's been assured is a real winner. We'll call this the "UltraHype Growth Fund" (which goes by the ticker BLECH). Over the past ten years, the BLECH fund has returned 11.2% annually. This is the starting point on the return on capital, but sadly not the final figure. The fund charges are very high – a 1.8% management fee. This is subtracted from returns, reducing the returns to 9.4% annually. Let's be generous and assume there are no additional costs like a load fee of 5.5% or 12b-1 fees or redemption fees.

The return on capital number will be 11.2% of $25,000 or a return of $2,800. From that, we subtract the 1.8% management fee or $450. This leaves the individual with a net return of $2,350. Another way to calculate it is 11.2% - 1.8%, which generates a return on capital of 9.4%.

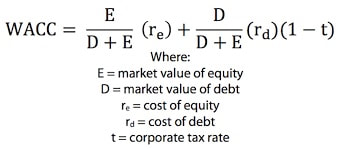

It should be pointed out here, calculating the weighted average cost of capital and return on capital can be - and usually is - far more complex. It helps to have a calculator or Excel spreadsheet handy. For instance, the actual formula looks like this.

So, where does this leave our individual? Did their move of taking a cash advance on their credit card pay off by investing in their expensive, hot-shot growth fund? The answer is a clear no. Their return on capital of 9.4% was swamped by their cost of capital of 20.15%. While it may seem obvious to any investor, it's important to point out this is a terrible use of capital.

Cost of Capital and Stock Valuations

Having your return on capital exceed your cost of capital really shouldn't be that profound of a concept for individual investors, professional money managers, or senior corporate executives. Is should also be pretty clear that rising input costs in calculating your cost of capital will lead to higher cost of capital. The dramatic movement in treasury yields cited earlier will dramatically impact a company’s cost of capital. With rising Treasury yields, many company’s suddenly began to see WACC exceeding ROC in their returns. These changes should have been seen in valuations if investors were taking these changes into account. The exact opposite has happened. Except for the sharp drop in valuation in the spring of 2020 and their subsequent - and relatively rapid - recovery, the trend in stock prices has been nearly always upward.

To apply this concept and see this disconnect in real terms, I want to use a holding in many of Nintai Investments’ individual portfolios - SEI Investments (SEIC). In December 2019, we estimated the company's weighted average cost of capital was roughly 9.4%. In that calculation, we included the federal funds rate of 1.87%. At that time, we estimated the intrinsic value of the company's stock was $55.20 per share. It was trading at roughly $66.00 per share or approximately 20% above fair value. By any standards, the stock was not a compelling buy. By December 2020, we estimated the company's weighted average cost of capital at roughly 7.9%. Nearly all the decrease in the WACC was the drop in the 10-year note yield. In our calculation, not much else changed. Revenue was flat, free cash flow was down slightly, and publicly traded shares were down slightly. There wasn't much to change valuation except the drop in the funds rate. But, boy, did that change our valuation. The $66 per share in December 2019 had jumped to $73 per share in December 2020. With the stock trading at $56 per share, the company was now trading at 23% below fair value - an enormous change in roughly one year. What had been a moderately overvalue company was now trading moderately below intrinsic value. On these numbers, we purchased shares in our portfolios. What a difference a year makes.

But our example doesn't end there. The exact opposite happened from October 2020 to March 2021. The 10-year note rate jumped 0.53% in October to 1.63% just six months later. The example we just showed went in the exact opposite direction. With such a massive jump in the 10-year rate, companies' valuations took a whopper of a hit. SEIC's valuation dropped from $73/share back to $61 per share. With shares trading at $60 per share, they were now at fair value instead of 23% below intrinsic value.

Talk about a whipsaw! In a little over 16 months, SEIC went from moderately overpriced to moderately underpriced to roughly fair value, all due mainly to changes in the 10-year Treasury note yield which then impacted the company's weighted average cost of capital. SEI Investments wasn't the only company that saw its valuations affected by its drop in the weighted average cost of capital. Every company in the public markets was impacted – some more than SEI, some less. Throughout all of this, overall yields didn't move much. The 10 Year US Treasury note yield was 1.73% on December 3, 2019, 0.92% on December 1, 2020, and 1.45% on March 1, 2021. But there was quite a gap between highs and lows. In August 2020, rates hit their low 0.52% and hit their high in December 2019 at 1.93%.

It's important to note that the markets overall were minimally impacted by these changes. From December 2019 to March 2021, the S&P 500 gained 25.4% rising from roughly 3150 to 3850. This even includes the massive drop in the spring of 2020 when the S&P dropped nearly 30%.

What This Means

For all this data and heavy reading, you might be asking yourself at this point what this all means. It's a good question and an important one to answer. The most important lesson to understand is that having cost of capital exceed return on capital is not a recipe for outstanding long-term stock returns. It should be common sense to any investor, but roughly one-third of all publicly traded companies currently have WACC exceed ROC. Somebody is investing in these companies, so not everybody has learned this lesson. Here are some other learnings to think about.

WACC and ROC Must Be Measured Together: I have to concede that I searched for companies with extremely high ROC at the beginning of my investing career but never screened them for WACC. There is a particular bias that a company with high ROC couldn't possibly have even higher WACC. It happens, though. And like any other company with a negative ratio, it's a company that doesn't generate value. Always remember to look at both ratios, not just one.

The 10 Year Treasury Yield Has a Big Impact: I used to denigrate investors who took a lot of time looking at macroeconomic issues because I felt they play a minor role in the business. I was right about that. What I was wrong about is that it plays a massive role in the stock. Remember: sometimes, a company's stock (and its price) has little to do with the company. This type of disconnect happens all the time. A significant rise in the 10-year note rate can drive up the cost of capital, making a dollar in the future worth a lot less. While the company might remain the same, its intrinsic value might decrease significantly. Never lose sight of the role of interest rates in valuation.

In the Short Term Voting Machines, In the Long Term Weighing Machines: Having said that interest rates could affect valuation, it's important to remember the longer the holding and the greater the business's success (through quality and value) the less the impact of interest rates will be. This is a convoluted way to say that time and business excellence overrides the shorter-term impact of interest rates. Being patient and allowing time to work its magic can dramatically reduce some of the risks (but not all!) associated with cost of capital.

Conclusions

For any long-term value investor (and what other kind is there? “Short-term value investor” is undoubtedly a contradiction in terms), the ability to find a business and management team that can produce value over a decade or two is the means to creating investment gains. The underlying foundation of this value creation is the ability to have the return on capital far exceed the cost of capital. Given time and allowing for the weighing machine of the markets to work their magic, companies can become compounding machines for their shareholders.

Understanding the dynamics of what constitutes the cost of capital and its relationship to return on capital is one of the most powerful concepts to a value investor. Looking at both and understanding the drivers of each, an investor has the tools necessary for making the best investment decisions possible. Will the markets always agree with you? Absolutely not. But an investor can go to bed each night fully understanding their investment has created value that day, that week, that month, that year, and hopefully the next decade or two.

I look forward to your thoughts and comments.

DISCLOSURE: Nintai Investments has no positions in any stock mentioned.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed