- Samuel Johnson

In my career in the investment field, Ben Graham sits isolated at the top of the mountain in terms of impact on my thinking and models. That said, a near second has been Jack Bogle, founder of Vanguard. Perhaps no other person in our lifetime has set the standard for ethics, created value through cost savings and brought so much education to the investor class (maybe Warren Buffett(Trades, Portfolio) but I would propose his actual investor reach has been smaller).

One of Bogle’s top issues is management fees and what he so eloquently refers to as the “tyranny of compounding costs.” Much like Johnson’s eponymous widower, Bogle has been tenacious in his view that investing in any situation with high fees is the triumph of hope over experience.

As an investment adviser, inevitably one of the questions you will be asked is how much you charge for fees. In addition, I’ve had many people ask us how we came up with the number we used at Nintai Partners (which was 0.75% of assets under management). We think this is a topic that doesn't get nearly enough attention. But rather than discuss rates per se, I wanted to use the space in this article to discuss the equity risk premium (ERP) in the context of management fees.

At the Nintai Charitable Trust we see the relationship between the risk premium and management fees as a vital measure in potential returns, management alignment with investors and a component of portfolio risk management.

The equity risk premium

The equity risk premium is simply the extra return required by investors as compensation for owning equities in the place of U.S. Treasuries. Many individuals use both historic (as calculated by the difference between the two over a defined period) and future (estimates of future returns for both classes) measures. Since 1802, the ERP has averaged roughly 3.5%. It has ranged from 0% to 5% in roughly half of all rolling 10-year averages. It has only consistently exceeded the high end during the periods ending between 1947 and 1970[1].

John Graham and Campbell Harvey of Duke’s Fuqua Business School issue a fantastic report on research conducted each quarter on the estimated equity risk premium. In their latest 2015 report[2] the estimated risk premium was 4.5%. Put another way, investors are currently demanding a 4.5% return over the current U.S. Treasury rate.

At the Nintai Charitable Trust we think (perhaps too much) about risk on a daily basis. If the ERP is currently 4.5% we look for any advantage we might have in reducing risk – not increasing it. And let's face it: the higher the amount you pay in fees the more these eat into the risk premium. Which brings us back to management fees, their calculation and their impact on risk for your portfolio.

Fees and investment returns

If an investor demands a 4.5% risk premium to invest in equities, it stands to reason the individual will look to increase the return in any way possible. This includes items that have a negative effect on returns – management fees, trading costs, etc.

Don’t think this makes a difference? Let’s take three funds to show management fees and their impact on the ERP. The first is the Vanguard 500 Index Investor shares. This fund has a total management fee of 0.17% and estimated trading costs of 0.05% for a total rate of 0.22%. The second is the Sequoia Fund with a management fee of 1.0% and estimated trading costs of 0.75% for a total rate of 1.75%. The last is the Gotham Absolute Return Fund with a management fee of 2.15% and estimated trading costs of 2% for a total rate of 4.15%.

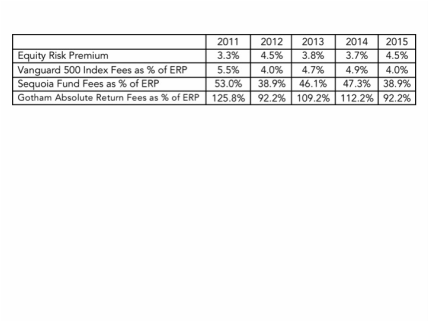

Looking at the data as provided by Graham and Harvey, we can compare management fees and estimated trading costs as a percentage of the equity risk premium for the years 2011 through 2015. For the Vanguard 500 Index costs made up approximately 4% to 5% of each year's ERP. A typical actively managed fund represented by the Sequoia Fund consumed roughly half of each year’s ERP. Finally, the Gotham Absolute Return Fund (a new fund we projected backwards for the years 2011 through 2014), costs would consume an astounding 100% or more of the risk premium.

When investment managers charge higher management fees and create high trading costs, they chew up the risk premium required by investors. Higher costs increase risk. It’s that simple. At Nintai Partners we charged 0.75% for several reasons. First, we didn't have back-end operations we needed to support. Second, we traded so rarely our costs on this front were minimal. Third, we firmly believed the proposed rate was adequate compensation for the value we added to our investors. Last, we saw anything higher as a shifting of risk to our investment partners.

Investors should be rewarded for taking risks. When those rewards are disproportionately shared with investment managers, the investor disproportionately takes on risk - and far too little reward. Much like Johnson’s widower, hope triumphs over experience. An experience that history has taught him – and investors – that the outcome is not likely to be to their advantage.

[1] The numbers here are provided by Jack Bogle in his classic “Common Sense on Mutual Funds,” revised edition, 2010, pp. 92-107.

[2] “The Equity Risk Premium in 2015,” John R. Graham and Campbell R. Harvey, Fuqua School of Business, Duke University, National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER); Duke Innovation & Entrepreneurship Initiative, Oct. 1, 2015

RSS Feed

RSS Feed