“There are three emotions that will really do you in as an investor – hope, greed, and fear. The first two will lock you in making you think you are a real genius, while the third eviscerates your investment return. You can never fully avoid these, but strengthen yourself to take advantage of them.” – John Rutherford

“Only when you combine sound intellect with emotional discipline do you get rational behavior.” – Warren Buffett (Trades, Portfolio)

Some recent articles by our favorite writers – Grahamites and Science of Hitting – got us thinking about an issue we write about every three or four years – emotions and data in investing. It seems about the time of every market top (or at least 6 of the last 3….), we write an article on the ability to face down your own fears and make money the only way great investors do – purchasing stocks at a substantial discount to fair value. It seems so easy. Wait for a really significant correction, step in, and purchase some great stocks. The rest is investment history. Or at least that's what they say.

Reality has a way of getting in the way of such elucidated thinking. The bottom line is that the vast majority of investors take in far too much information, overreact far too vividly to too much data, blame others for their poor results, and begin the cycle all over again. For the first instance, in a classic study[1] by Richard Thaler, subjects managed an imaginary college endowment consisting of two mutual funds. They could choose how often they received information about fund performance and how often they could trade. The experiment simulated 25 years of investing. The results were clear - participants who received information once every five years, and could trade only that often, earned returns that were more than twice those of participants who were updated monthly and could trade that frequently. The bottom line was that the frequency and amount of data availability directly correlated to poorer returns.

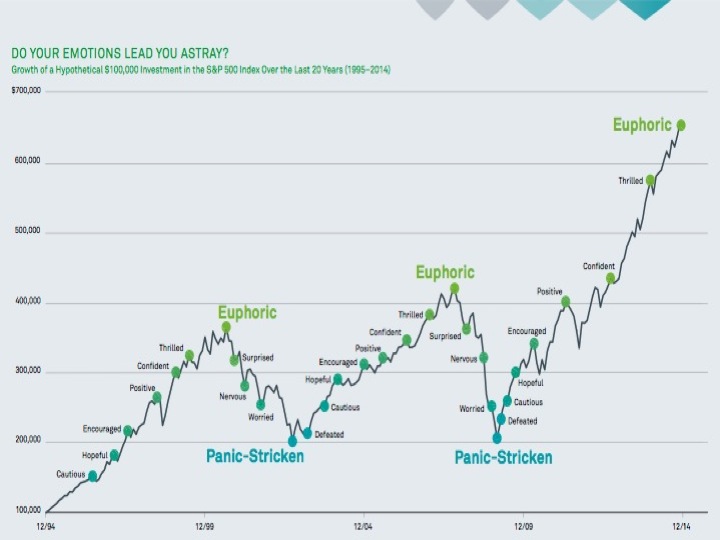

Not only do investors who receive too much data trade more frequently and obtain worse returns, their emotions generally proceed in a rather standard format, rising from a state of panic to euphoria. You can imagine where the latter leaves us in the market cycle. In a recent study by Blackrock[2], the investment team created an outstanding graphic demonstration of the emotions by many investors during stock market phases. By 2014, we feel we’ve seen this movie too.

Why This Matters

So what can we do about this (un) virtuous cycle that seems to repeat itself every decade? How do prepare ourselves as individual investors and set up systems to prevent these behaviors. We would humbly recommend the following steps.

Focus On Value, Not Price

A great start is shutting off every television, radio, SATlink, or Bloomberg in your office right now. We then highly suggest using whatever model you choose – DCF, DDM, etc. and calculate the value of each and every one of your holdings. Do this irrespective of any knowledge you might have related to its price. Then – and only then – use Yahoo! Finance to look at the price. If your estimated value is above its current price, then think long and hard about whether this position is worth holding. At Nintai, we have no Bloomberg and no television in our office. Our focus is constantly on value – a cold hearted evaluation on the specifics of the company. If a prospect meets our criteria, than and only then, do we look up its price relative to its value. After that, we simply use a limit order to watch the price for us. 99% of our time is spent on value not price. 99% of what you hear on the financial media is about price rather than value. Turning it off will be one of the best investment decisions you will ever make.

No One But You Pulls the Trigger

In the final analysis no one makes the decision to buy or sell but yourself (unless you use an investment manager). Your decisions will ultimately produce the short and long-term investment outcomes that have such an impact on your financial future. Poor outcomes are a measure of two things – your emotional ability to make rationale buy/sell judgments and your ability to weigh value versus price of each investment you make. Poor returns are a reflection of failure in one or both of these attributes. Only you can remedy these problems.

There’s No Better Time than the Present

With markets at all time highs and investors reaching euphoric levels, there is no better time to shut off all the media, load up on corporate 10-K/Qs, and roll up your sleeves to evaluate each of your holdings. It’s amazing how everyone (and I mean everyone!) can allow great news to bleed into our assumptions and business cases for our holdings. Be ruthless in your evaluations, invert your estimates, and build in truly horrific assumptions. After you’ve completed this, silently slip back to your computer and check the price. After evaluating your intrinsic value against price, make the decision to buy, hold or sell. Then shut the computer off. However you choose to implement this model, do it now. There is no time better than the present. We can’t guarantee investment success with this method, but we would suggest the odds are in your favor of outperforming the vast majority of individual investors and money managers.

Conclusions

We live in an age where information is available 24/7. Most of this information provides absolutely no function in evaluating value of our specific holdings. More importantly, the information is provided in a format as to play on our emotions. Finally, we live with a human brain that looks in every possible way to blame others for our failures yet make us feel like genius for our successes. These three factors play an inordinate role in the truly horrific losses occurred every so often when we face significant market corrections. By limiting our data intake, creating models with our own intellect focused on value, and building systems to minimize emotional responses, we can prevent such losses. In the final analysis, these steps will help (but not guarantee) make you an investor that outperforms the markets in the long term.

[1] http://www.kiplinger.com/article/investing/T031-C000-S002-investors-beware-the-pitfalls-of-too-much-informat.html#vVckyWKBZKIp7JFL.99

[2] https://www.blackrock.com/investing/literature/investor-education/investing-and-emotions-one-pager-va-us.pdf

[3] “Looking for Someone to Blame: Delegation, Cognitive Dissonance, and the Disposition Effect”, Tom Chang, David H. Solomon, Mark M. Westerfield, October 2014, available at SSRN

RSS Feed

RSS Feed