- Hedgephone

“Capital markets are the essential tool to make capitalism work, and most importantly, work well. Keynes said that when the capital development of a country becomes a by-product of the activities of a casino, the job is likely to be ill-done. Has anyone noticed that asset bubbles are coming more frequently with greater impact? Who would have thought we could have a technology bubble and crash followed by a real estate bubble and crash only seven years later? My greatest fear is that speculators are using the markets to offload their risk to an increasingly complacent public market.”

- Richard Addison

Recently I wrote about the concept of “responsible capitalism” in a reply to Howard Marks’ memo “Growing The Pie” (the article can be found here). One of the subjects I discussed was the changing role of capital allocation in the public markets. More specifically, I discussed the role of increasing complexity and financial engineering that assures that hedge funds and large institutional investors make a great deal of money while putting a great deal of risk on the individual investor and reducing their share of the pie.

It made me think of the story of two tourists who had purchased tickets to participate on a safari. The first tourist smirked at the second when he noticed his seat was the closest to the ground. He said to his companion, “I may have paid more, but I’ve got the best seat to see the animals”. His companion smiled, took his friend’s ticket and turned it over. It read “This seat - while having the greatest views also carries the greatest risk. Please be advised you may need to vacate your seat in the case of an animal attack”. After reading this, the second tourist smiled and said, “It isn’t always the price and the view. Sometimes it’s where you sit that does you in”.

The Changing Role of the Capital Markets

If Wall Street’s job is to allocate capital “for the singular purpose of maximizing shareholder returns”, sometimes I’m confused by the transactions I see announced on the financial news. In a well-functioning market, capital should flow to companies and concepts that have the greatest potential return to investors. As an example, take two fictional companies that have filed S-1s with an intention to go public over the next 90-120 days. The first company - Acme Rubber Band (DOINK) – generates $15 of earnings on $150 of revenue (a P/E ratio of 10), earns 15% return on equity, and has been growing revenue at roughly 11% annually over the past 10 years. The second company - Shmaltz Quick Fix Solutions (STEAL) has not produced positive earnings in its history, has negative return on equity, and burns through roughly 33% of its cash balance each year. All things being equal, one would think that Acme should have an easier time underwriting its initial public offering (IPO) than Shmaltz. In Acme Rubber Band’s case, we have a company that has generated significant returns for its initial (private) investors. The company is now seeking to access capital to help ramp up sales, marketing, staffing, or production. Additionally, it may use IPO proceeds to pay off short or long-term debt. Finally, they may use some of the proceeds to pay off earlier investors should they seek to exit their current position. In essence, Acme has gone to the markets to continue their growth story and seek new investors and capital in the continuation of that journey.

Schmaltz Quick Fix is really quite a different story. In this instance, the company may try to pass this off as looking for investors in their growth story, but they really don’t have one. Their finances are a wreck, their growth is not profitable, and there is a fair chance that any new capital will be used to pay off previous investors and keep the doors open. In the words of Hedgephone, this IPO is an exit strategy for previous investors, not a growth strategy for new investors.

Investors - who by their very nature must be allocators of capital - should seek two things when making a decision to invest in an IPO. First, which company has the best chance of achieving above average returns on capital in its operations and strategy? The answer to this question is vital to value creation and investment returns in the long term. The choice between Acme and Schmaltz couldn’t be starker. Second, how is the deal structured, how will the capital raised be employed, and how will it drive returns for investors? This question tells us which investors will see a return and which that won’t. In other words, where are they in the safari seating plan? Without knowing the exact deal structure it’s hard to make a fully documented choice. However, with the historic data we have, I’d say the circumstances certainly lean in Acme’s favor.

This type of discussion isn’t entirely academic in nature. Over the past twenty to thirty years, the idea of Schmaltz being taken public – on a major exchange - has gone from being laughable to entirely plausible. What might have been seen as a lark on the Pacific Stock Exchange in 1980 is an almost everyday occurrence on either the NYSE or NASDAQ today.

A Working Example: Chuck E. Cheese

We can move the discussion from the hypothetical to the real world by using an example of a recent IPO announcement for a company known by many readers with young children – Chuck E. Cheese. The company was started in 1977 with its first Chuck E. Cheese Pizza Time Theater in San Jose, CA. After filing for bankruptcy in 1984, it was acquired by ShowBiz Pizza Place, In 1998 it became CEC Entertainment. In 2014, the company was acquired and taken private by Apollo Global Management. Apollo paid roughly $1.3B for CEC’s restaurants in 47 states and 14 countries. The company also has 144 Peter Piper Pizza units in six states and Mexico.

The IPO Announcement

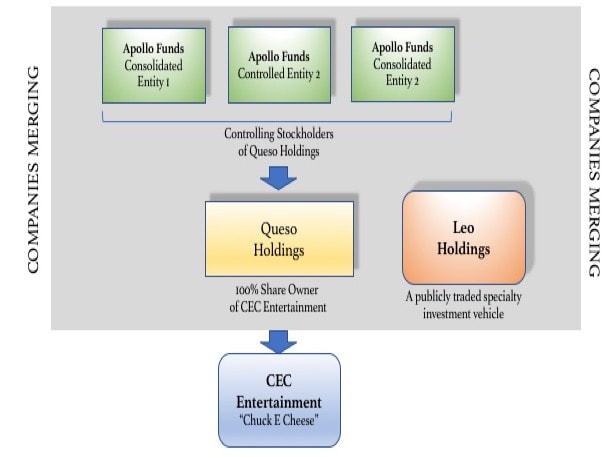

After 5 years of ownership, Apollo is looking to cash out and make a return on its initial investment. CEC announced that its parent company would merge with Leo Holdings, a special-purpose acquisition company. The new company will be known as Chuck E. Cheese brands, and it will trade on the NYSE under the ticker CEC after the deal closes sometime late in the second quarter. In their announcement, the companies stated the new organization will have an enterprise value (market cap + debt – cash) of $1.4B. After all of the accounting and corporate engineering shenanigans, Apollo will retain 51% of the new corporate entity.

The IPO announcement reads as follows:

CEC Entertainment, which owns the Chuck E. Cheese pizza/entertainment chain expects to start trading with an anticipated initial enterprise value of ~$1.4B or 7.5x the company's estimated 2019 adjusted EBITDA of ~$187M. CEC and Leo Holdings (NYSE:LEO) a publicly traded special-purpose acquisition vehicle, along with CEC parent Queso Holdings, agree to combine. Queso's controlling stockholder is an entity owned by funds managed by affiliates of Apollo Global Management (NYSE:APO).

Immediately following the closing of the proposed transaction, Leo intends to change its name to Chuck E. Cheese Brands and trade under the ticker symbol CEC. Apollo funds won't be selling any shares in the transaction and will continue to be CEC's largest shareholder with about ~51% ownership. Concurrent with the consummation of the deal, additional investors will buy $100M of common stock of Leo in a private placement. After any redemptions by the public shareholders of Leo, the balance of the ~$200M in cash held in Leo Holdings' trust account, together with the $100M in private placement proceeds, will be used to pay transaction costs and de-leverage the CEC's existing capital structure.

For those having a hard time following the financial engineering, I’ve enclosed a chart that graphically demonstrates the organizational transactions that gets us to the new/old Chuck E. Cheese.

Over the last four quarters, comparable sales have improved sequentially, rising from 1% in second-quarter 2018 to 7.7% in first-quarter 2019. However, overall revenue increased just 1% last year to $896.1 million as its store count fell from 754 to 750. CEC reported operating income of $50.8 million last year which seems adequate until you realize the company had $76.3 million in interest expense. Suddenly CEC moved to a net loss of $20.5 million. CEC has nearly $1 billion in debt on its balance sheet, which explains its crushing interest expense and its inability to make a non-EBITDA profit.

A Lesson to Be Learned

If one to were to take an old-fashioned view of the capital markets, capital should flow to companies and their investors that will provide the best opportunity of achieving outstanding returns over the long-term. That’s certainly the way I look at the role of the markets. With that said, I find very few opportunities in the IPO market. I think there are far too many “exit” vehicles rather than “growth vehicles”. Far too many deals are structured to make money for past investors, not future investors. That doesn’t mean I don’t think there is a role for the public markets or the IPO process. Far from it. They provide a vital role in capital liquidity and access to the capital for small and upcoming ventures. But as an older – more prudent – investor, I look to invest with management where both internal and external shareholders have the opportunity to compound their returns over an extended period of time.

Value investors should never lose focus on the two words that make up their occupation. “Value” means purchasing an asset at a discount to its estimated intrinsic value. “Investor” means utilizing time and the power of compounding to achieve adequate returns over the long term. When a company comes to the public markets as a result of financial engineering and accounting gimmickry – to paraphrase the words of John Maynard Keynes - the job is likely to be ill-done. To put in the context of our big game safari tourists, always make sure you purchase the ticket with the best seating – not from the lion’s standpoint, but from a survival standpoint.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed